Published: December 4, 2015

Last Updated: December 31, 2015

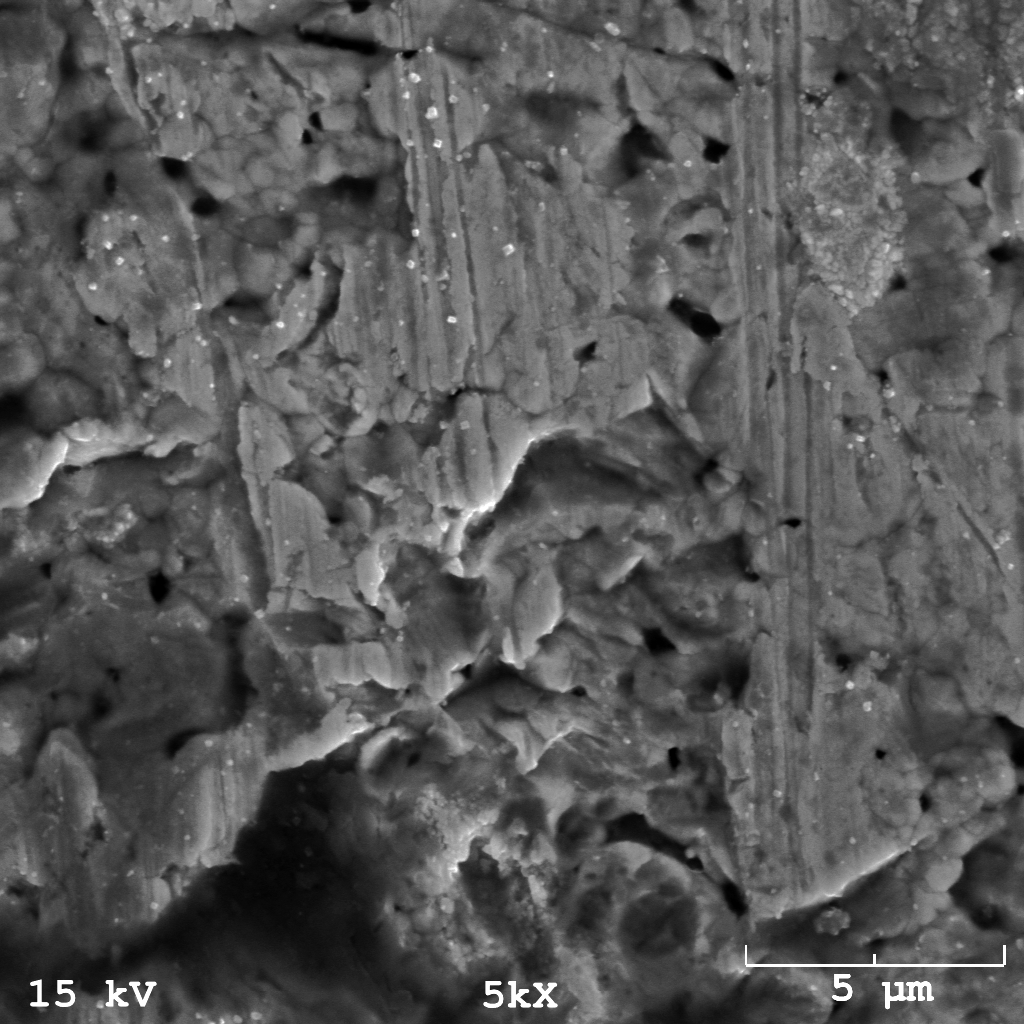

MICROSCOPIC SCARS

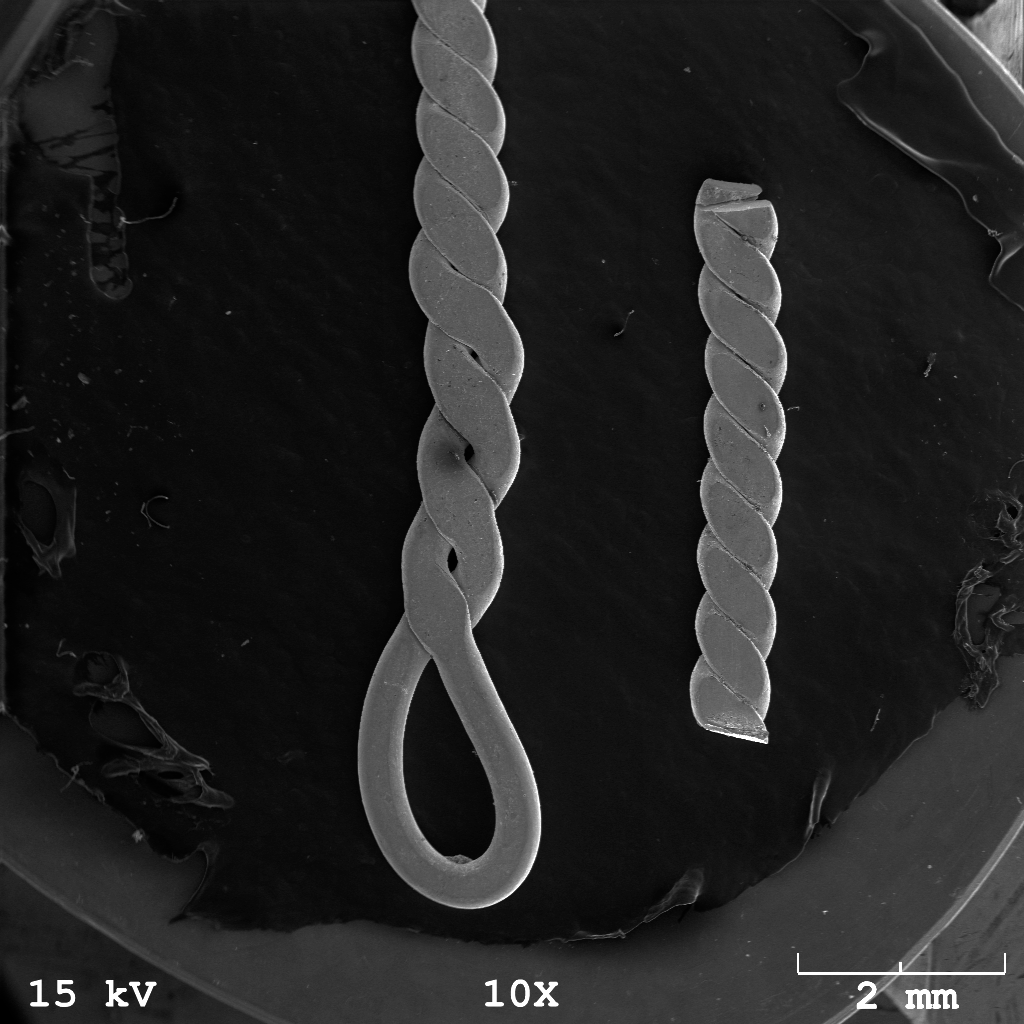

Beginning as part of Sculpting Science, a joint project of the Herberger Institute’s Ceramics department and the School of Life Sciences, at Arizona State University, to represent science through the lens of art, this piece is based on a section of fine silver filigree wire under extreme magnification. The goal of the project was to find new and interesting ways to represent microscopic data. The artists were given the opportunity to have objects of their choosing scanned by a high-resolution scanning electron microscope. The resulting micrographs were the inspiration for the art. Lindsay selected a section of filigree wire as an attempt to integrate metals and ceramics, her main mediums, into a single piece by exploring the structure of metal beyond normal human perception.

CONCEPT

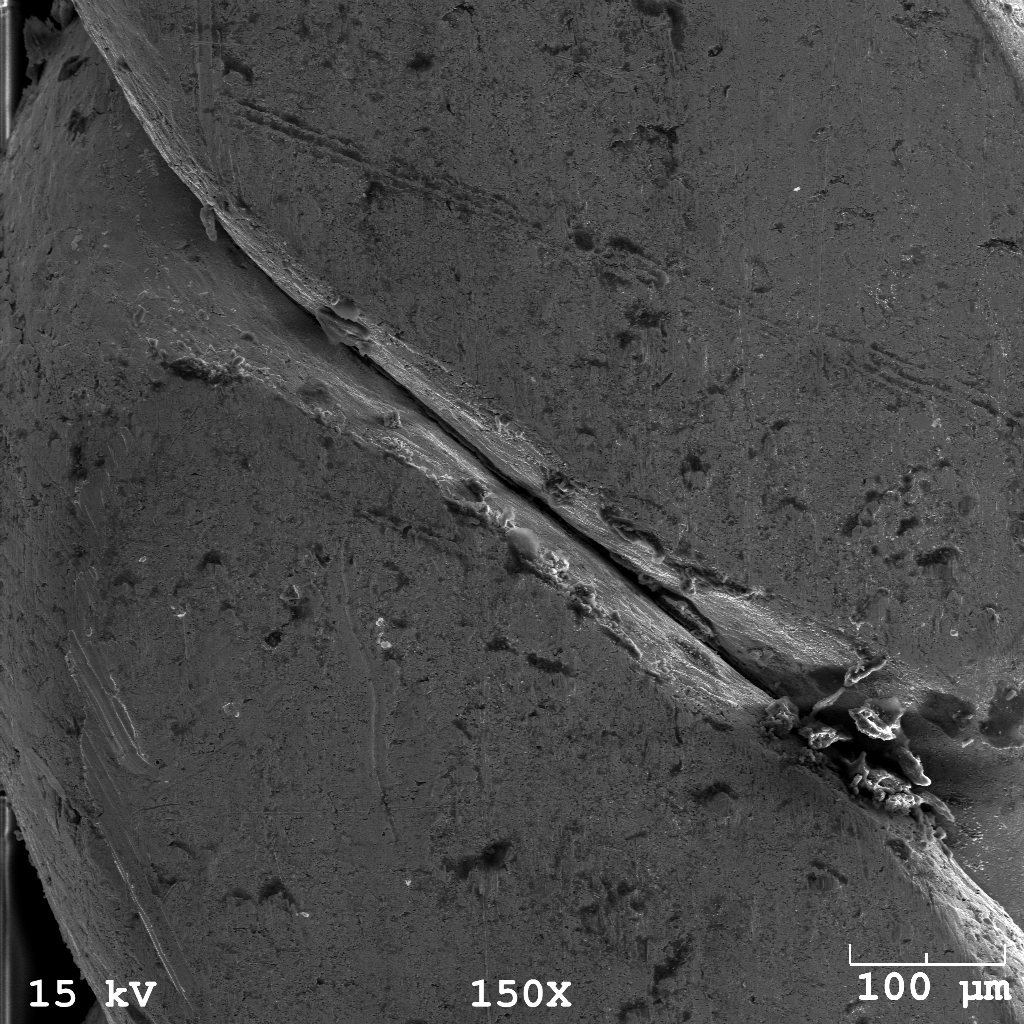

Using the revealed textures recreated in ceramics on the surface of a body cast of her own torso, and separating each section with fine silver wire inlay, this piece captures multiple aspects of the concept and properties of silver, and herself. Microscopic Scars acts as an explicit self-portrait because the intersection of the two mediums, with the scientific inspiration and a copy of Lindsay's own physical form, combines important aspects of her life, personality, and physical being. The body cast was made with an earthenware clay body, a clay with a porous finish, because she has an affinity for unglazed ceramic forms as part of her interest in ancient and prehistoric arts and the natural beauty of raw earthenware.

The piece rebels against formalistic composition by juxtaposing trapped open space in the filigree section with organic shapes that do not trace the literal form of the body, but instead mark their own delineated scars. The slight contrapposto stance, in combination of a torso missing all limbs, is a nod to the surviving relics of Classical statuary. In composition the work hangs visually unbalanced, having smooth cream-colored naked clay and silver inset dominating the right side, unequaled by any visual or textural elements on the left. The asymmetry is continued with the visual weight conveyed by a red iron oxide stain focusing on the textured lower left. This forces the eye to stay in constant motion across the piece drawn along the silver lines, which is replicated in form through the filigree section. The tension created fatigues the mind to rest upon the smooth “upper” layer, representing the external, routinely viewed skin.

TECHNIQUE

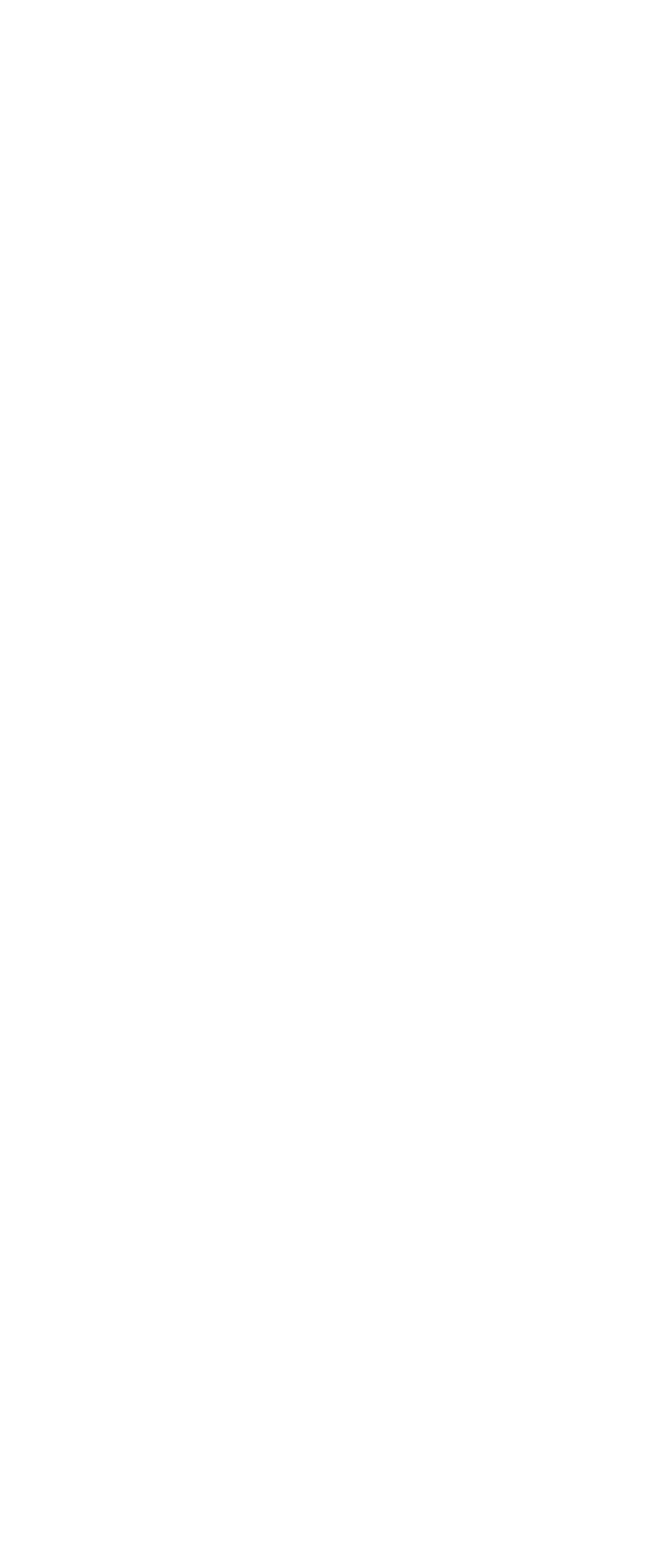

Body casting, a highly involved process, requires help of a trusted assistant, in this case Liz Lohr. Multiple layers of plaster wraps are applied to the torso, and then backed with pottery plaster. After setting for a week, clay is hand-pressed into the mold. To remove the piece from the mold requires that it be divided into several parts, each individually removed and reassembled. While the clay is pliant, lines are incised for later insertion of silver wire. Once firing of the ceramic is complete, fine silver is pressed into the lines. The filigree is created from a flattened two-strand braid of small-gauge round fine silver wire. It is then shaped into the desired spirals and free-forms. The individual sections are soldered into place in the sterling silver frame. The representation of tiers of magnification is accomplished by using texture and varying concentrations of red iron oxide deposited onto the surface. The silver inlay creates boundaries that visually separate each layer. The filigree section is a further abstraction of depth and pattern.

CONTENT

The piece appears to be stitched-together, like a patchwork person. The silver is reminiscent of the Japanese technique of kintsugi, repairing broken ceramics by filling cracks with precious metals, thereby increasing both the material and sentimental value of the object. Through the care taken after breakage, the work becomes more beautiful and cherished. The silver as borders was planned; however, serendipity often plays some part in the creation of art. Through the process of firing, a section of the sculpture was damaged when a small pocket of trapped air expanded in the kiln with violent consequences. Deliberately embracing kintsugi, Lindsay replaced the absent space with the elaborate filigree form.

Due to Lindsay's graduation, this piece was not shown as part of the Sculpting Science exhibition, and so it was never viewed in the explicit framing of scientific data expressed in novel ways. From conception through the fatalistically flawed but remastered completion, this work ranged beyond the scope of the project, not merely showing representations of data, but making visible the artist's own microscopic world. The surface on one's own psyche, like even that of highly polished silver, when examined carefully, is not as smooth as it might appear. In contrast to a culture that simply discards flawed or broken items, embracing and magnifying those imperfections can bring into focus the true worth, aesthetics, and beauty of an object.

Last updated: December 4, 2015